"Andy Guhl is a master at what our modern media environment has long succeeded in casting out:

he is not a user, but a subversive arranger and luddite thwarting technological conversion."

Excerpt from book essay

"The (historical) sound of

images", Peter Kraut, 2013

"The (historical) sound of

images", Peter Kraut, 2013

Andy Guhl

Ear Lights, Eye Sounds.

Expanded Cracked Everyday Electronics

Ear Lights, Eye Sounds.

Expanded Cracked Everyday Electronics

Edizioni Periferia, Lucerne / Poschiavo

ISBN 978-3906016-28-3

272 Pages, Hardcover.

ISBN 978-3906016-28-3

272 Pages, Hardcover.

This book about the experimental musician Andy Guhl at first looks loud and somewhat confusing, but this is part of its programmatic intent. It is a reference to Guhl’s musical credo: for four decades, he has often moved on the border between music and noise with his disassembled and rewired everyday electronic devices. In addition, two important design decisions remind the reader that a book, like live music, has a temporal dimension: the left hand pages show full-bleed still images from audiovisual performances by Guhl, creating a strong rhythm as one leafs through; and on the right-hand pages, a continuous stream of various images and texts flows from top to bottom in a seemingly mechanical layout. On these pages, the unusual paper, reminiscent of carbon paper, is extremely susceptible to

the traces left from being touched and scratched. The inevitable rapid wear on the volume, particularly on the cover, transforms each book into a unique art object.

Tan Wälchli (Berlin/Zürich), © BAK, 2015

This is a monograph of the Swiss musician Andy Guhl whose career began in the seventies with free improve, before embracing electronics until, in 1983, he eliminated any classic instrument in favour of what he called “cracked everyday electronics” with his band Voice Crack. This practice incorporates the use of radios, turntables, transmitters, dictating machines and other items, cracked open and manipulated through gestures and light, in an ante-litteram circuit-bending. This book embraced the challenge to properly embody this kind of practice and content in its design, winning the Swiss Design Award. First there is a clear division between left pages, filled with visuals, and the right pages where the text is included. Even if the text is subaltern to the preponderant visuals, and is split into small chunks, it is still perfectly legible. Of note in the publication are 100 reproductions of Guhl’s “Colliding Sediments” works; stills from the audiovisual performance THE INSTRUMENT; as well as images from concerts, original sketches and illustrations. Consistent with the fragile nature of the instruments at the core of his practice, the book is printed on a special type of paper which is sensitive to touch, easily scratching or slightly deteriorating, perfectly archiving in a unique way the spirit of Guhl’s work.

Neural Nr. 55/2017

→ Neural

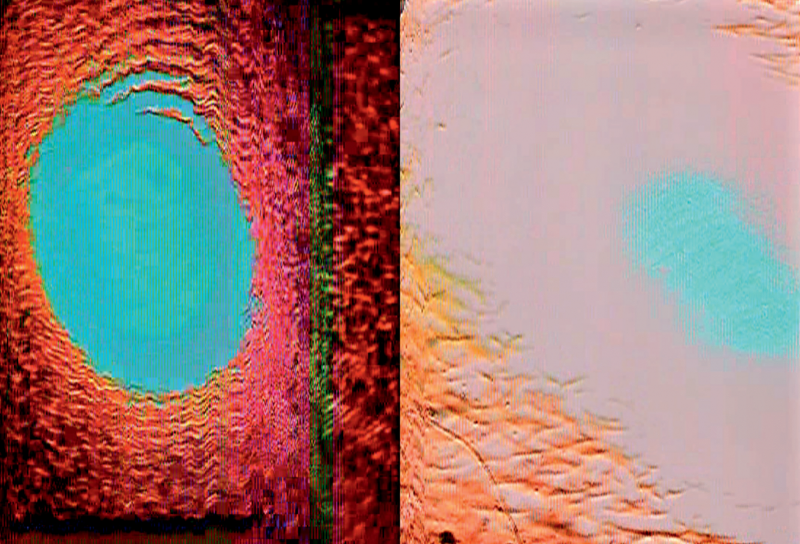

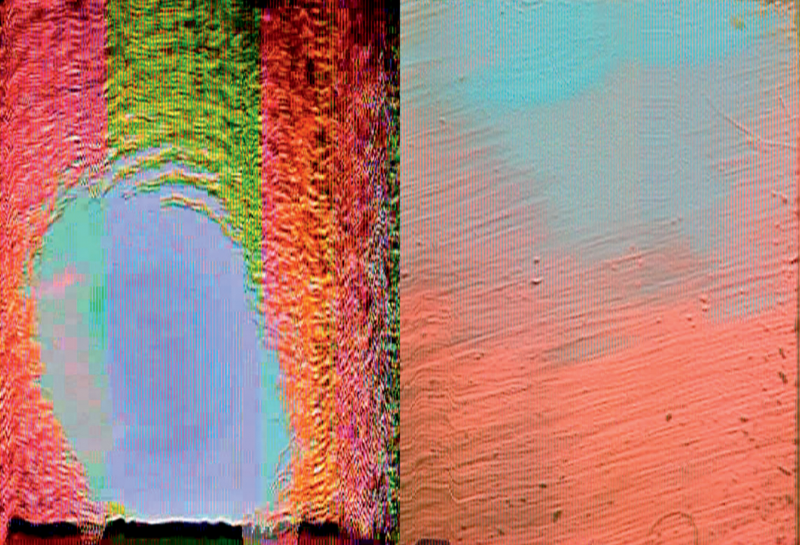

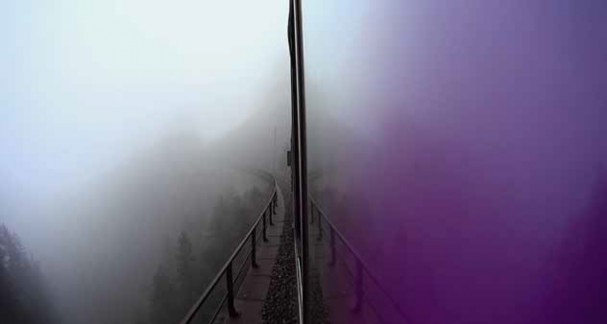

(1–3) Making the audiovisual recording for the exhibition My first sonic Lok at Bahnmuseum

Albula, Bergün, 2013. Installation of various analog sensors to record the vibrations and electro-magnetic waves during the operation of the locomotive on the world-famous Albula route. Gion Caprez, Andy Guhl. Live sound mix in the driver’s cab of the locomotive RhB GE 6/6 704 «Davos», 65-ton, 2400 HP engine, 11 kV, 16.7 Hz. (4) Eight different converters from physical waves—used as microphone or speaker. (5–6) My first sonic Lok, 170° video still, from the exhibition at Bahnmuseum Albula, Bergün.Taken from the audiovisual recording of a train locomotive ride on the Albula line. Visual of the cracking sounds of this high-voltage machine recorded by a video camera attached to the window of the locomotive.

Andy Guhl

Ear Lights, Eye Sounds.

Expanded Cracked Everyday Electronics

Ear Lights, Eye Sounds.

Expanded Cracked Everyday Electronics

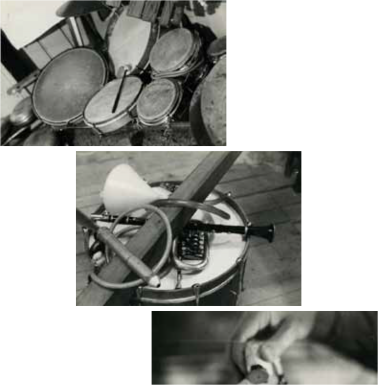

(1) Do-it-yourself drum set with homemade percussion material, such as kitchen utensils, hot water bottles, curtain rods, wooden sticks, and children’s toys. (2) The combination of traditional and homemade instruments and a big drum head creates a new world of sounds. (3) Detail of crimping wheel used to produce vibrations on small drum head. (4) Preparing the membrane with motors from children’s toys running on 4.5 volts +- .

Andy Guhl

Ear Lights, Eye Sounds.

Expanded Cracked Everyday Electronics

1952

Born in Gossau, Canton of St. Gallen, Switzerland

1960– 61

Pre-electronic: as the first-born, my sister should have learned the piano, but because my mother was busy with the children who came after, she dismantled the piano and took it apart. I helped to put the framework of the piano on the floor with the strings facing upwards. We little ones weren’t allowed to play with the piano, which we could have been disgruntled about. When I was eight years old, I went down into the dark cellar and generated sounds with the strings on the damp soil, which was also where we stored the vegetables.This changed the whole store room into a resonance chamber.

1962

My very first hacking of hardware: I took apart my grandmother’s clock.

Great inspiration: instrument with all its parts laid out. One of the causes of transmission distortions can be found in the complicated way in which electronic apparatus is put together. Here you can see 7 the 2,076 parts of a television.

(1) Collection of calling tools: whistles and pipes to imitate and attract birds, deer, and frogs, 1965–2013. (2) Indian bowed violin, to explain the principle of resonance

in acoustic and electromagnetic instruments, Resonatorprinzip workshop, New Delhi, 2009. (3) Bagpipes: inspirational object, interference tones, steady, breathy sound.

1965

I was living at my parents’ house in Gossau, St. Gallen; I loved to listen to medium- and short-wave radio.

Phonoradio: Experimental contact as line-in amplifies vinyl sounds from the turntable and, shortly after, it is as if radio waves are being mixed with jazz sounds, for example Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz, 1970—a gift for my The Instrument!

1965

Important moment: Working with my mixing desk, Phonoradio.

I had a record player, but because it was too expensive to get an amplifier with loud- speakers, I had to use the loudspeaker I had—the one from the transistor radio.

I only had this little radio because my mother, who had two of them, dropped one of them and it broke. I was allowed to have it and I repaired it.

Until 1968

Primary and secondary school in Gossau

Physics lessons were a source of inspiration for my own experiments with magnetism, loudspeakers, continuous current, cables, low-current soldering (my father worked for the East Switzerland telephone network, Halser AG); I listen to medium- and short-wave radio in the evenings, North African voices and music (my uncle lived in Oran then, so this was his music!).

1968

Failed to pass entrance test at the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Applied Arts), St. Gallen

1969 –71

Practice room Bleichli, cellar room under Africanarts, with Bernhard Leuthold, piano and percussion, amongst others, Josef Kopf, lyrics, Heidi Beck

1968 –72

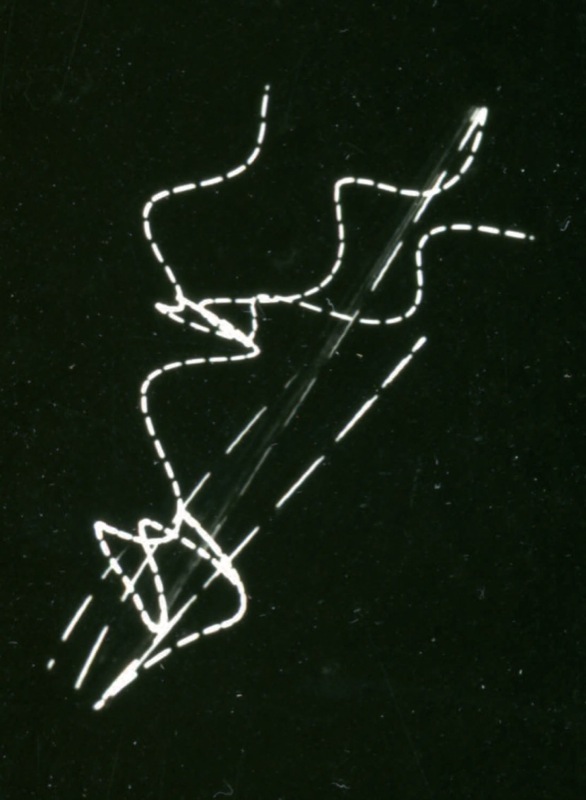

Heliographic images with light and oily emulsions, heliographs and ink drawings.

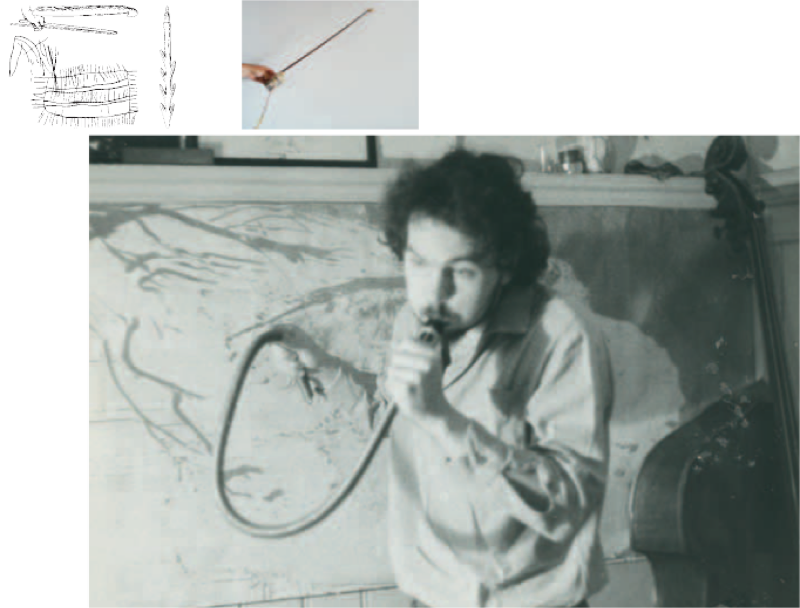

(1)Source of inspiration: ethnological literature on work tools and living customs.

(2)Resonance bow: membrane and bow hair with a resonance element to be used on the double bass, pure acoustic sound. Andy’s resonance bow for double bass playing.

(3)Background: Heliogramm, 1969, action painting, 200×90 cm, developer blown onto

light-sensitive paper. I did this painting while training to become an architect. Playing 11

the “federphone,” a homemade instrument with a bass clarinet mouthpiece and a tube…

1968 –72

Apprenticeship to become architect.

I loved working on the helio machine, it was a kind of magic. Music with friends at home and in the forest with drums and flutes. During my apprenticeship, I bought a double bass for CHF 100, which I borrowed from my grandmother.

I loved working on the helio machine, it was a kind of magic. Music with friends at home and in the forest with drums and flutes. During my apprenticeship, I bought a double bass for CHF 100, which I borrowed from my grandmother.

1972

Town of St. Gallen, Musik Hug, enjoying the latest jazz records in the listening room and no money to buy them.

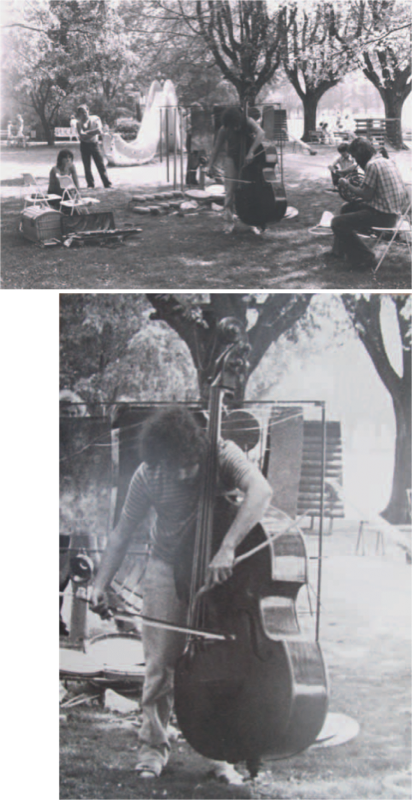

Open-air concert in Bühler/Heiden

Making series of black and white photographs of musical equipment and work in the darkroom with black and white photography.

Creation of own concert posters, which were one-off artworks, for the concerts in St. Gallen.

Open-air concert in Bühler/Heiden

Making series of black and white photographs of musical equipment and work in the darkroom with black and white photography.

Creation of own concert posters, which were one-off artworks, for the concerts in St. Gallen.

(1/2) Urban Urbaniak, open-air concert in Bühler/Heiden, Appenzellerland. Inspiration from playing music at different places changes the music and anatomy of listening. (3) Andy Guhl (left) and Norbert Möslang (right) improvising on their self-built instruments.

1972

First of three children with Lisa.

Moved to flat in St. Gallen, where the living room was used as a practice room above a printer’s shop; rehearsals with Gieri Battaglia, Norbert Möslang, Herbi, Bernhard Leuthold, playing music at night and at the weekends, rehearsals.

Moved to flat in St. Gallen, where the living room was used as a practice room above a printer’s shop; rehearsals with Gieri Battaglia, Norbert Möslang, Herbi, Bernhard Leuthold, playing music at night and at the weekends, rehearsals.

(1) Background: Andy Guhl, left, Norbert Möslang, right. Foreground: Lisa Guhl, Camillus Guhl. Improvising at Freudenberg, St. Gallen. (2) Andy playing the contrabass on his terrace in old town St. Gallen. Photographed by friends visiting from the Netherlands.

1972 –74

Trio Möslang-Guhl-Battaglia perform “free music” in the Klosterhof, St. Gallen Concert, canton school in St. Gallen

1972

Bought another “secondhand double bass” (100 years old) for CHF 100 from violin maker Sprenger. “Secondhand” for a string instrument doesn’t exist—the older the more precious. It was repaired in one week at the violin workshop under the expert supervision of Mr Christoph Sprenger himself. Decided to continue working as a draughtsman rather than become a violin maker.

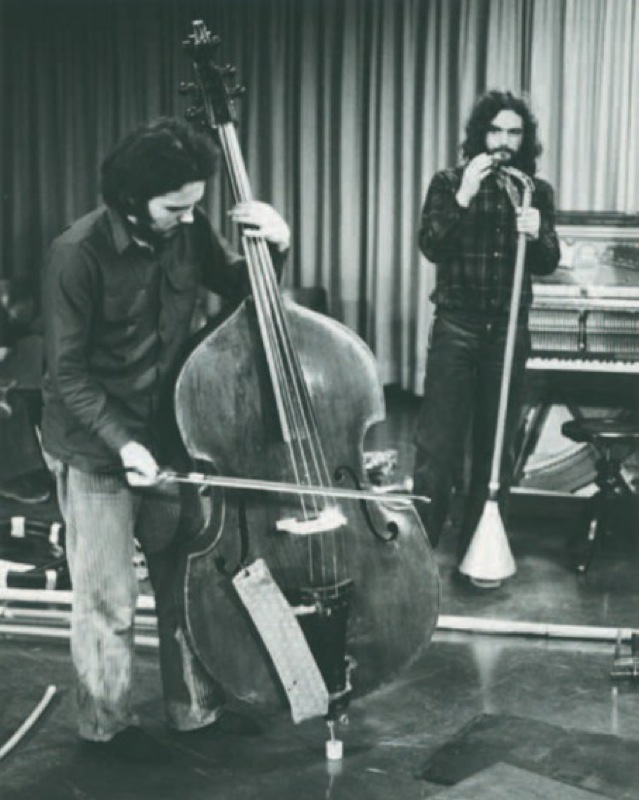

Concert and workshop, teacher training, Rorschach

Concert and workshop, teacher training, Rorschach

Möslang/Guhl, teacher training workshop, Rorschach. Andy on double bass, Norbert on tubular saxophone.

1972

Concert, Institute ofTechnology (ETH) Zurich

Concert with competition, Uster amateur festival qualification

Concert with competition, Uster amateur festival qualification

Amateur jazz festival competition.

1974

Outstanding creativity award, Augst amateur festival (Irene Schweizer and Johannes Anders, amongst others, on the jury)

VSETH-Foyer, Zurich (meeting with Anton Bruhin and Stefan Wittwer) First public concert in a restaurant, Klosterhof St. Gallen: Andy Guhl, Gieri Battaglia, Norbert Möslang

VSETH-Foyer, Zurich (meeting with Anton Bruhin and Stefan Wittwer) First public concert in a restaurant, Klosterhof St. Gallen: Andy Guhl, Gieri Battaglia, Norbert Möslang

Acoustic concert, playing sitting on the floor inside the restaurant Klosterhof, near St. Gallen’s famous church. First public appearance in St. Gallen of Norbert Möslang, Andy Guhl, and Gieri Battaglia. Realizing how provocative freely improvised music was. Some people asked: “Can you also play correctly?” and they were relieved if there was a correct sound: “Oh, he can play correctly!” So the question came up for the artists: what is right/wrong in music?

Noise or Avant-Garde

by Gieri Battaglia

by Gieri Battaglia

I met the St. Gallen natives Andy Guhl and Norbert Möslang for the first time in 1972. Both were already active as musicians, and they were eager and happy to make music with me in a trio from that point. Our music should come into being “democratically” without a “boss.”We didn’t want to use a predefined distribution of roles, and solo accompaniment music, as in traditional jazz, was something we ruled out from the start.

In Andy’s practice room we had access to numerous brass, string, plucked string, and percussion instruments. From a little flute to a large cymbal, “everything” was there and we tried out all of the instruments as if we were “amateurs.” Sometimes Andy, Norbert, and I worked with a specific theme (a “composition”). This could be verbal arrangements or pictorial sketches. Other “pieces,” on the other hand, didn’t have a theme and came into existence spontaneously.

In due course, a certain favorite instrument “emerged” for each of us. Norbert liked to play the soprano saxophone, bass clarinet, and piano; Andy double bass, bass clarinet, and percussion; I personally enjoyed playing the trumpet, accordion, and piano.

Harmonically, everything was possible.Traditional major and minor chord scales were an option, but didn’t have to be used.We sometimes worked with tonal centers, occasionally with clusters (bunches of sound), often free-tonally.

Melodically, our music often wasn’t the kind that the average man in the street would find “nice.” Above all, the wind players created such high, shrill, screeching, whistling, squawking, and snorting tones—sounds and noises at which the distinction between sound and noise was not of any interest to us.

Rhythmically, our music ranged from a constant pulse to a free beat. Everything was possible. In this relation, we also didn’t let ourselves be constricted.We made music above all for ourselves.

In terms of dynamics, the music we were making at that time was perhaps a little “tight” when I look back on it today, but most of the time we played in the area between mezzoforte and fortefortissimo..

However, at that time we were very interested in experimentation. During our “sessions” there was often a cassette recorder playing.The results were listened to intensively, “checked,” discussed, criticized, improved.We were also curious and wanted to know and hear what other musicians and composers were doing. Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, and CecilTaylor. Ligeti, Kagel, and Stockhausen. Eric Dolphy, Sun Ra, and Alexander from Schlippenbach. Boulez, Cage, and Nono.We were also very interested in exciting and “real” folk music from distant lands.

Coming from a background of “absorbing” free jazz and contemporary music, we developed a personal music of our own, some of the time with our freely chosen rules. In the process, our sound creations came very close to those of the so-called e-music composers at times.

We were courageous and uncomprising: for that performance in the former Restaurant Klosterhof, we naturally appeared in everyday clothes, had long hair, and didn’t bring any music stands or documents with us.We had our repertoire in our heads. Our “treasure” was the shared experiences that we had acquired

as we played and practiced.There was no previously arranged program.We wanted to be anything but mainstream.We didn’t think about the audience.We played first and foremost for our- selves.The Klosterhof was full, the artists didn’t take a fee, entrance was free. Quiet as mice, the attentive audience followed our music. Of course, the reactions to it varied greatly, ranging from perceptions of our work as noise, caterwauling, and caco- phony to exciting, interesting, full of variety, new, avant-garde,

and modern.

1974

Practice room in a flat on Klusstrasse 20, St. Gallen

Han Bennink, Mischa Mengelberg, Alexander von Schlippenbach, Radu Malfatti, etc. as role models.

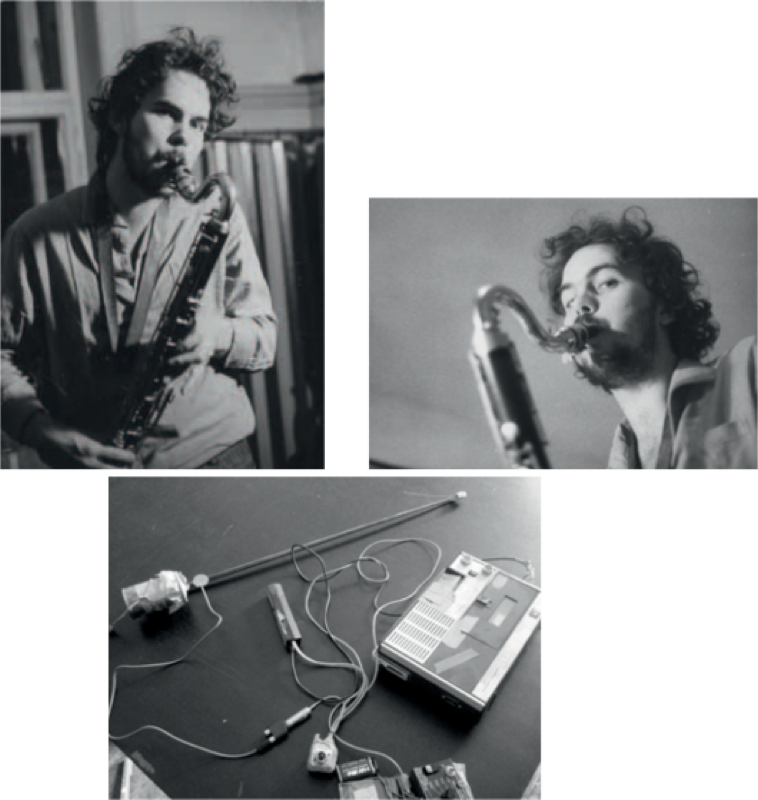

(1/2) Klusstrasse 20, practice room. Andy with bass clarinet. (1) Background: percussion

elements, brass curtain rods. (3) Andy’s hacked cassette tape player with wave modulation and piezopickup/resonance bow.

1974

Tümpel project and sine waves on LW, compact cassettes

Improvised musical performances with son Camillus and daughterTabea

Andy’s Tümpel project in his music room on Klusstrasse (Möslang/Guhl’s practice space). Layering and spatial storage of Andy’s various musical instruments offers sound-making possibilities. Audio cassette recordings used live as additional voices for Deep Voices, 1977.

1975

Jazz workshop, Basel with MKS radio recording, Music Cooperative Switzerland,

founding concert in Zurich (SUISA) applications for performing and creating improv music

Boys’ music concert in a marquee, Huttwil

Jazz workshop and concert, Buchs

Concert,Theater am Stalden, Fribourg

Concert, Modern Jazz, Zurich

Radio recording in the sound studio, Zurich

Gaskessel, Bern (meeting with Jürg Solothurnmann)

Nagold Amateur festival (award)

Concert, Bern, Zähringer

Boys’ music concert in a marquee, Huttwil

Jazz workshop and concert, Buchs

Concert,Theater am Stalden, Fribourg

Concert, Modern Jazz, Zurich

Radio recording in the sound studio, Zurich

Gaskessel, Bern (meeting with Jürg Solothurnmann)

Nagold Amateur festival (award)

Concert, Bern, Zähringer

1976

Kellerbühne, St. Gallen

Möslang/Guhl, Jazz festival, Solothurn

Möslang/Guhl, Jazz festival, Solothurn

Jazzdays Festival, Solothurn. Front: Andy on percussion; rear: Norbert on metal drum sheets.

1976

Concert and workshop, Lützelflüh Kulturmühle

MKS Festival Kellerbühne, St. Gallen

Concert, Lausanne

Concert, Zurich

Concert, Geneva

Concert, Basel

July 9, 22:30, radio programme DRS2, recording studio

MKS Festival Kellerbühne, St. Gallen

Concert, Lausanne

Concert, Zurich

Concert, Geneva

Concert, Basel

July 9, 22:30, radio programme DRS2, recording studio

“Musically Close to Zero and Zilch”

A Letter to a Swiss Radio Studio

by Franziska Kohler

The music of Andy Guhl gives rise to emotions, some of them vehement.This is shown quite distinctly by an incident from 1975. It took place in Studio 2 of “Radio Zürich,” as it was then known: on November 12, Andy Guhl and his duo partner Norbert Möslang met there with sound engineer L. to do some re- cordings.These were supposed to be broadcast in the context of the program Jazz Live—a show highly regarded on the Swiss music scene that ran from 1964 to 1984. Sound engineer L. was, however,

not able to appreciate the doings of his two studio guests at all and was indeed downright horrified: “Their playing is musically close to zero and zilch!” he said agitatedly in a telephone conversation with S.R.—a renowned music critic and jazz lover who was a big fan of the duo Möslang/Guhl and had brought them to Jazz Live. “I find it depressing and disappointing that you in particular are so very far from the mark,” L. said to S.R. If things had gone as the horrified sound engineer had desired, the sounds of the duo would never have been put on the air: he wanted to prevent the program from being broadcast.

He had, however, not reckoned with S.R.: in a letter toW., the production director of Jazz Live at that time, S.R. indicated that he was “depressed and disappointed” by L.’s scathing verdict.Through listing the awards that the duo Möslang/Guhl had already received at this point in time, he made it clear “that I am not as alone in my opinion as it might seem based on L.’s scathing critique.” And he continued: “It might be assumed that those responsible for the many concerts [...] were conscious and in full possession of their ear for music, their critical faculties, and their misgivings when they engaged this group, and/ or always gave them good or even very good marks in the jury evaluations.”

In S.R.’s letter, it is possible to read how hard experimental music was struggling for its right to exist at that time. It had to look for its place in a world in which music was predominantly assessed based on conventional criteria taught at conservatories. According to S.R., the duo Möslang/Guhl wins

over listeners with originality and creativity, “but an originality and creativity that (nevertheless!) develop according to their own individual laws outside

of the conventional maxims taught at conservatories, and find their way to a musical-creative field of expression to which traditional patterns and criteria of evaluation are apparently not able to do full justice.”

According to S.R., every expert should have an ear that is open to new forms of music. He also recommended, for instance, attending events that provide a platform for new and experimental music: “They contribute to jettisoning the ballast of the traditional, at least insofar as this ballast is no longer able to unnecessarily prevent one from accessing new forms of expression in music.”

Sound engineer L. also criticized the duo Möslang/Guhl for lacking conservatory training. S.R. had a clear opinion on this, too: “Conservatory training can undoubtedly help immensely, but it can—as has been shown again and again—also very much get in the way.”The fact that this training plays such a large role for L. “undoubtedly has only very little to do with the Möslang/Guhl duo, but very much to do with his own identity and his conception of himself personally, musically, and otherwise!”

How the production directorW. reacted to the sharp letter is not known.The recordings of Möslang/Guhl were, in any case, broadcast on Radio Zürich in the end—even if at an untimely

hour of the night.

1977

HansWerner Henze: Natascha Ungeheuer performance with bass clarinet in

the jazz group of the orchestra in Zurich

Concert, Bazillus Zurich, Concert, MKS Festival, Kellerbühne, Concert, Aarau, Concert, Modern Jazz Zurich, Concert, ArognoTI

Concert, Bazillus Zurich, Concert, MKS Festival, Kellerbühne, Concert, Aarau, Concert, Modern Jazz Zurich, Concert, ArognoTI

1977

Moving music material together using a hay cart

Jazz workshop, Basel FestivalTotal Music Meeting, FMP record, Deep Voices

Release, Deep Voices, Möslang/Guhl (LP FMP 0510, CD new edition 1988: Urthona 03)

First overseas concert, festival, first meeting with important international jazz musicians Free Music Festival, Berlin

Jazz workshop, Basel FestivalTotal Music Meeting, FMP record, Deep Voices

Release, Deep Voices, Möslang/Guhl (LP FMP 0510, CD new edition 1988: Urthona 03)

First overseas concert, festival, first meeting with important international jazz musicians Free Music Festival, Berlin

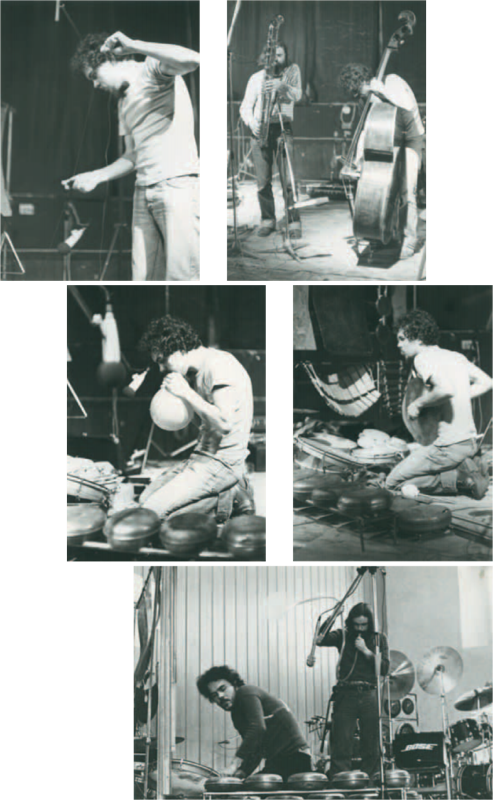

(1) Free Music Festival, Berlin, live recording of Deep Voices LP and CD. Nylon

string in a parchment membrane, played by creating friction on the string.

(2) Norbert on contrabass clarinet, Andy on double bass. (3) Andy blowing up

a balloon for different special sounds, hot water bottles in the foreground.

(4) Andy with his homemade drum set. (5) Andy on the floor with homemade percussion, Norbert with a homemade elastic trumpet.

When Jazz Started to Move

in New Directions in St.Gallen

by Richard Butz

in New Directions in St.Gallen

by Richard Butz

In May 1978, a longer contribution of mine appeared in the local newspaper, the St. Galler Tagblatt, to coincide with

the release of Deep Voices—the first LP from the Möslang- Guhl duo. In the article I criticized St. Gallen for being a jazz wasteland, but also praised it for producing some- thing new and radical that had hardly ever been seen up until then in this new duo. During this time we had a lot of contact and we met a lot of times in order to discuss and listen to new musical possibilities. In the years that followed, wherever I was in the world, musicians interested in expe- rimentation would mention these two musicians from

St. Gallen to me. I was very glad that they were so wellknown, and it evoked feelings verging on pride in me. In St. Gallen it took a while longer, and even today it seems to me that we know too little about Andy Guhl’s experiments and artistic excursions here. I always find myself thinking about that when we see each other in summer while swimming in the same bathing pools of St. Gallen.

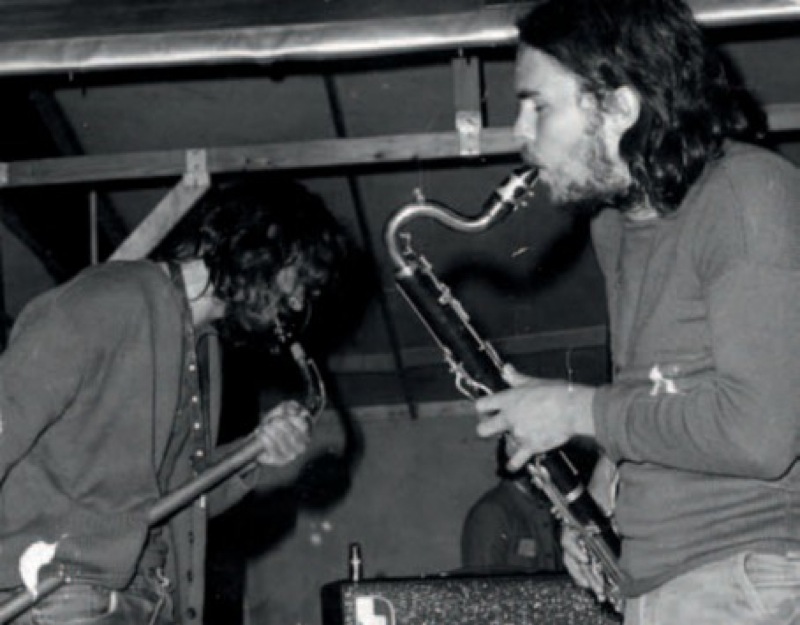

1977

Totentanz, concert in Basel

Totentanz, concert in Basel. Norbert with a tubular saxophone, which can be extended with an alto

sax mouthpiece; Andy with painted zinc plate and bow.

1977

Teaching himself animal noises (richiami) and ethnological music from all

over the world.Working with various sound colors, rhythms, and instruments. Own acoustic and electronic instruments, development of pickups and light and magnetic wave sensors for live music.

1978

ZurichTheater at Neumarkt Modern Jazz Zurich; Concert, Aarau; Concert, Liestal Practice room, Steigerstrasse 8, St. Gallen, heated room

1979

Möslang/Guhl, open-air performance, Biel

Practice room/studio 1 at Mühlensteg 3, shared with Norbert Möslang

Meditation at studio 1, Mühlensteg, St. Gallen.

(1/2) Open air concert, Biel. Andy on double bass, Norbert on

flugelhorn; background: percussion instruments.

1979

Concert, Produga, Zurich; Festival de Jazz, Mulhouse; Conservatory, Bern

Studio concerts, studio 1, Mühlensteg 3, St. Gallen

Production and release of the Uhlang cassette

Studio concerts, studio 1, Mühlensteg 3, St. Gallen

Production and release of the Uhlang cassette

1979

Release Brissugo, Möslang/Guhl (Uhlang Production, cassette UP 01)

Concert in the studio of Max Oertli, Mühlensteg 3, St. Gallen

Own music production with a cover design that included packing paper, corrugated cardboard cartons, stamp letters, and rubber jar seals

Concert in the studio of Max Oertli, Mühlensteg 3, St. Gallen

Own music production with a cover design that included packing paper, corrugated cardboard cartons, stamp letters, and rubber jar seals

1980

Etchings, series of “cosmic landscapes” with etching and drypoint techniques

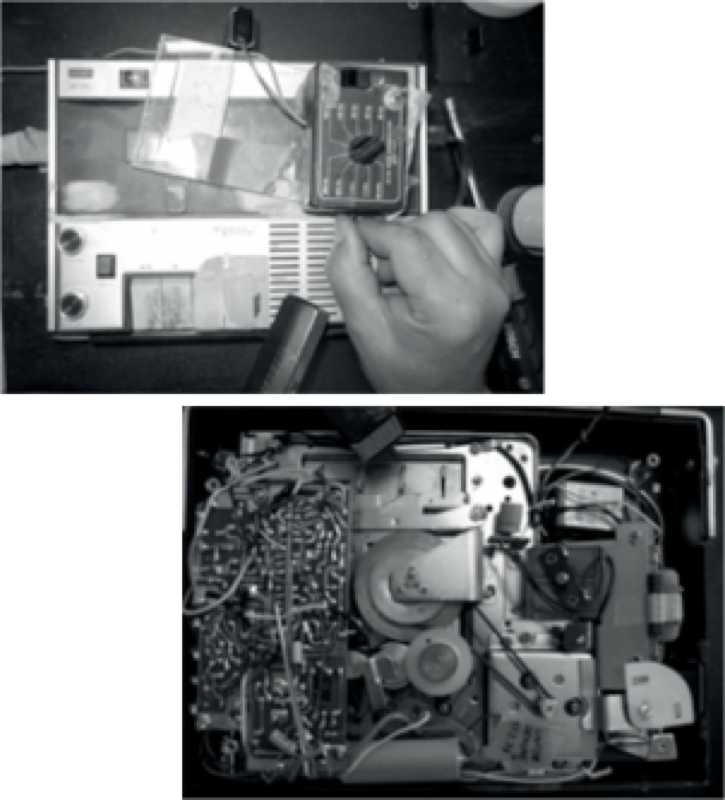

(1) Acoustic transformer: cassette tape player. Two-key faulty circuit makes an audio amp with sound modulation via microphone and sine wave oscillator, used with Andy’s double bass and viola in concerts at theWIM, Zurich. (2) Electronic acoustic transformer: electroni- cally re-forms the sounds of my instruments via feedback and sine wave feed. Electronic transformation occurs as instrument tone is fed into sine wave; diversion of the sine wave oscillator to the microphone allows me to mix in the sound from the viola.The open case means I can scratch tapes by touching the motor as the tape turns.

1980

Draht 1, Society of Swiss Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (GSMBA)

vernissage at Stadttheater, St. Gallen

Interesting meeting with a professional association

Interesting meeting with a professional association

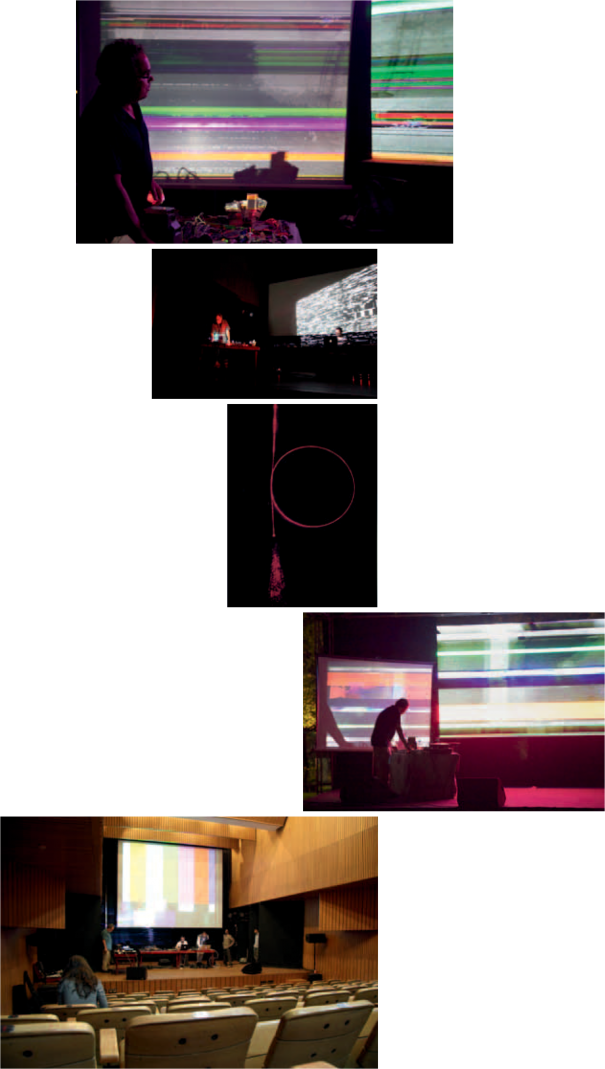

(1–3/5–6) Performance of The Instrument at Swiss Embassy, Sound Reasons Festival, New Delhi.

On the right, there is an LED panel. (4)This optical fiber with a diameter of 126 micrometers and

a “core” of 50 micrometers is 30 centimeters long.The fiber—illuminated here by argon laser thanks to an ingenious photographer—emits a conical spindle from its coherent, monochrome beam of light.The beam of light needs one nanosecond (one billionth of a second) to go through these 30 centimeters at the speed of light (300,000 km per second). For this reason, the computer bodies have to be positioned close to each other to prevent interference. (6) At the French Embassy, Sound Reasons Festival, New Delhi.

Sound Reasons

A Sound Art Festival in Delhi

by Ish Shehrawat

A Sound Art Festival in Delhi

by Ish Shehrawat

As a medium, sound art encompasses a number of activities and forms, such as sound installations, noise, radio art, experimental electro-acoustic music and musique concrète, to name but a few. Each of these forms has its own details and depths and should be analyzed according to its own distinct aesthetics. However, the lines dividing them all are often blurred, and their variations can be experienced and appreciated through a continuous involvement with them over time.The characteristics of continuity and redefinition are complex yet vital to the positioning of sound art as a truly post-modern art form where the process of creation and the subjectivity of the listener are the main focus.

Sound Reasons is a multidisciplinary domain and, as a record label and a sound festival, it brings together artists from all over the world to interact, exchange, and reflect on their practice.The festival, which is more of a hybrid process that brings together diverse practices, is in its second year now. I first conceived the idea for it with Chandrika Grover from the Swiss Arts Council, Pro-Helvetia,

in 2010 while curating a few Swiss sound artists and musicians who were show- casing their work in Delhi.The process, however, soon spiraled into something more, resulting in the first Sound Reasons Festival, for which I invited artistsTapio Makela (Fin), Jio Shimizu (Jap) and Dr. Nigel Helyer (Aus),Yashas Shetty (Ind) and Robert Millis (US).The Swiss artists included were: Robin Meier, Bernd Schurer,Thomas Peter, and Hans Koch.We were able to continue this process into 2013, where the line-up for the festival included, amongst others, SaloméVoegelin, Andy Guhl, Grischa Lichtenberger, Eisentanz, edGeCut and diFfuSed beats.

Looking to the future, we envision a physical space for Sound Reasons in the form of a creative/production-based studio that will facilitate collaboration between artists and enthusiasts to build a vocabulary for the medium and the creation of synergies between the artists and the community.With this space we also hope to shed light on more con- temporary jazz artists likeVijay Iyer andTheWhite Rocket, to name but a few. In 2013, I was able to collaborate with Andy Guhl on some of the live performances and his visuals added an extra immersive dimension to the performance.These performances were well-received by the audience at the festival here in India, as it was the first time that they had experienced a performance like this. We are looking into some live collaborative work in the future, and we also recorded a studio session as a trio along with Jasch in Delhi which was over 110 minutes of sounds and music.This was a very interesting improvised section and we plan to release it in the early part of 2014.

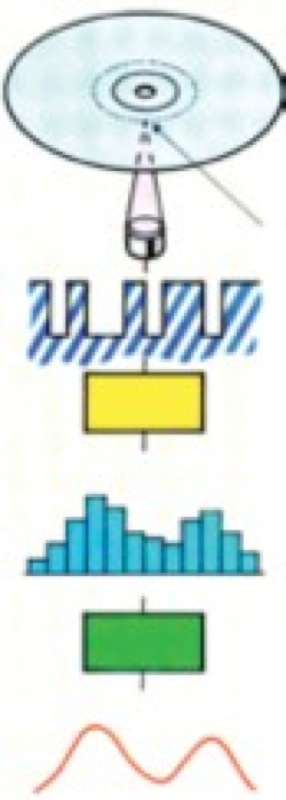

From top to bottom: An optical signal becomes an audio signal through a digital analog transmitter (yellow).The opposite of The Instrument’s system.

S y n c h r o n o u s Tr a n s f o r m a t i o n s

Hacking Expectations and Conventions

by Jan Schacher

Hacking Expectations and Conventions

by Jan Schacher

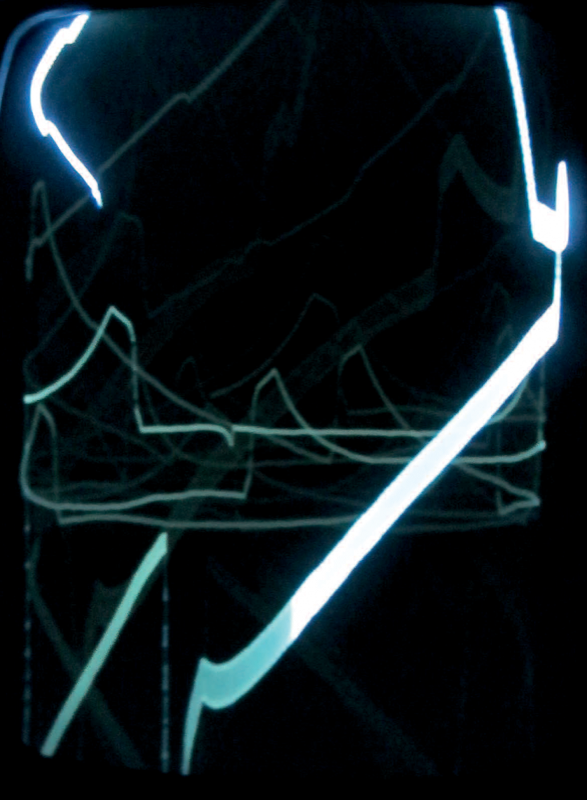

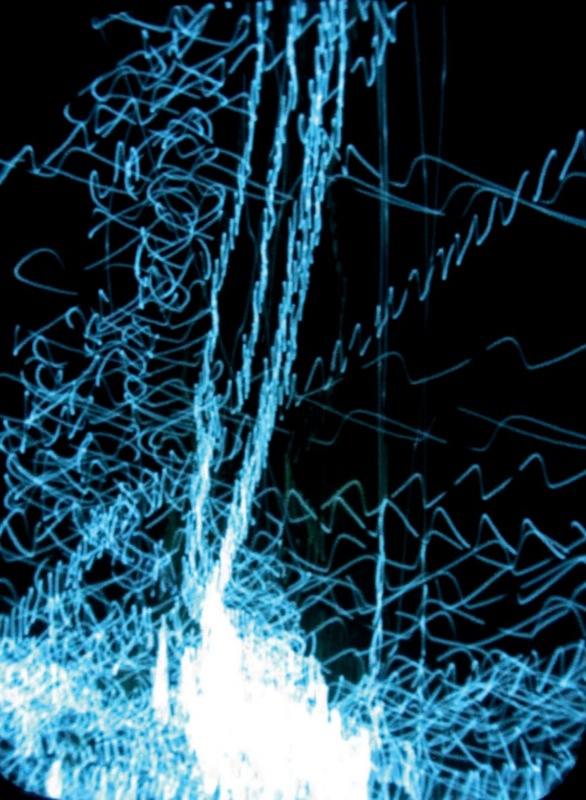

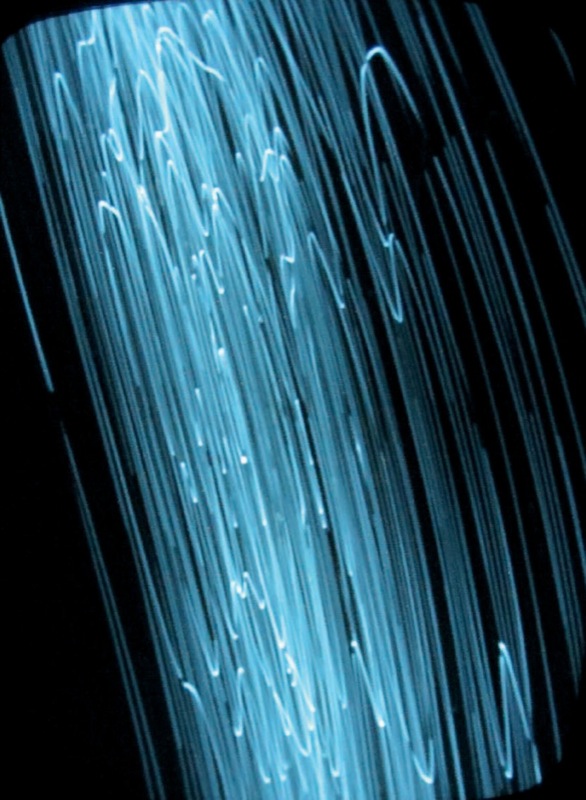

When I was watching Andy Guhl perform recently, what immediately struck me was the unity and integration of his actions and materials through the instrument. He seamlessly moves from shaping sound to modifying lights: he is exploring the boundaries of the devices, circuits, and signals that make up his material, and is deliberately shaping the space and time of his piece, the surface and the structure of his “time canvas.”This, to me, seems characteristic of his extended and long-term occupation with hardware hacking and live performance.

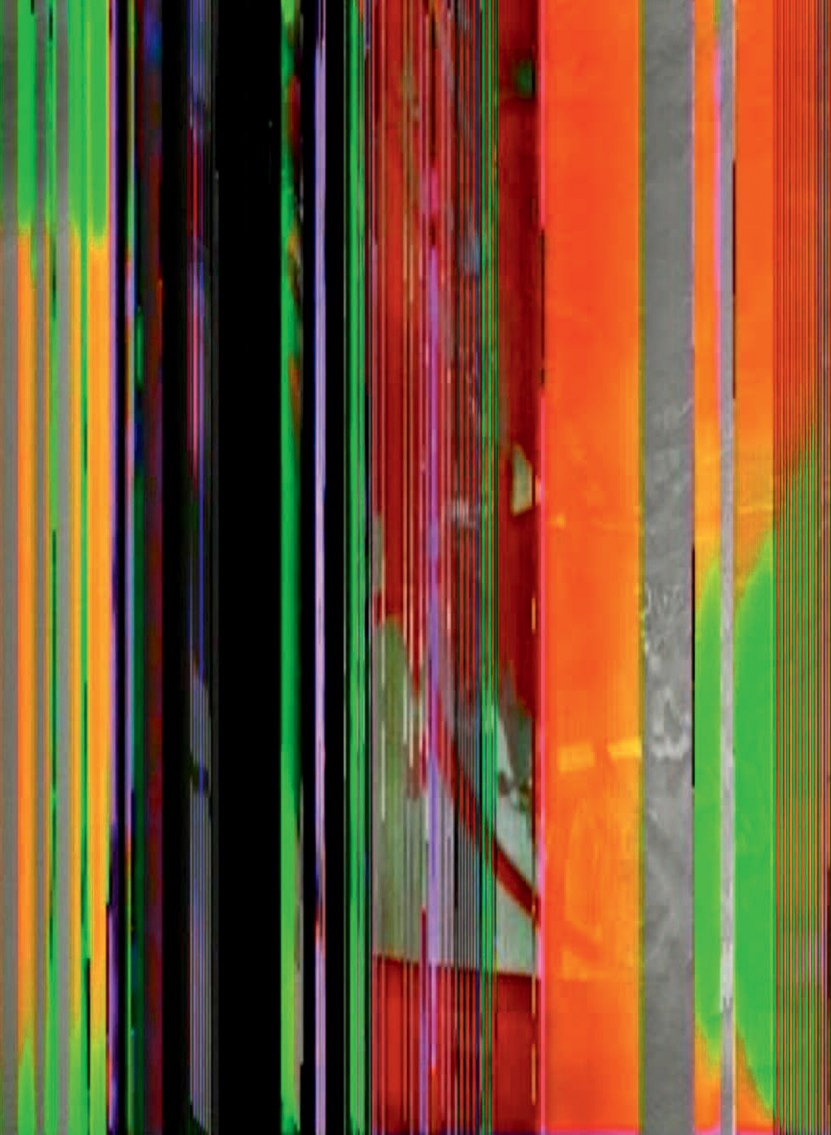

The tight coupling of bent electronic circuits, sonic and visual materials, lights and actions generates a synchronicity that is hard to match. In the feedback loop of light generating sound and sound modifying light, Andy becomes the third pole, the agent of transformation. With a short decisive action, he generates form and gives a direction to the sounds and the images. By continuously rearranging how the sound- and video-signals mix, criss-cross, and fold back on themselves, he shapes his instrument, in order to transform the piece. It’s not just that the instrument is synchronous on a technical level, he is handling it in a manner that makes this linkage evident. A particular experience and dedication is necessary to master these tools and instruments, and flashes of insight and inspiration are elementary to go beyond what these materials inherently afford.

The glitch in synchronization of the video-signals with the video projector corresponds to the fissures, or to use a biographically charged word, the cracks in the purposes of the various devices. It opens a gateway that exposes the inner deficiencies of technology and its lack of potential to generate something genuinely new in an emergent fashion. It is Andy’s agency that extends the meaning of these assemblages, that gives them a shape during the performance, a shape that arises and exists purely in the moment on stage. And although he creates a bubble that resembles a perpetuum mobile that feeds and propels itself forward, without his presence it would not refer to outside elements, the system would continue forever, circling around an orbit of its own making. It is through Andy’s deliberate actions that it opens up, connects, creates reflexions, and enters into an oscillation with our perception.Thus he continuously negotiates the boundary between the physical action, the simple analog tools and complex electronic circuits, which, even though they contain highly integrated silicon logic, do not execute code but merely embody it in their basic function.

By operating with codes, other than digital ones, he hacks not so much the devices and contraptions that are unfortunate enough to land on his operating table. It is much rather the codes of usage, the limits of intended purpose, that are transgressed, in order for the parts to be recombined in a larger pattern that generates a different meaning in his hands.What I think he is really hacking are the expectations of what an instrument should be, the way things are supposed to be done on stage, and what is permissible by convention for an artist to embody in the domain of performance.

Synchronization is the core theme of Andy’s work, the link between elements and phenomena, between the senses, between the physical and the abstract, and between action and experience. Ultimately it is this link that provides us with an opening intoAndy’s world, allows us to feel connected, patched in, and possibly even hacked ourselves. Art has

its own logic, and can only ever produce a unique solution to a subjective call, thus fulfilling the potential of a singularity, valid truly only for its maker. Yet, in Andy’s performance, on stage, and for us as his audience, by sharing the moment and living it through his art, meaning emerges that need not be universal and needs no apparent logic for us to be touched

by it.

2013

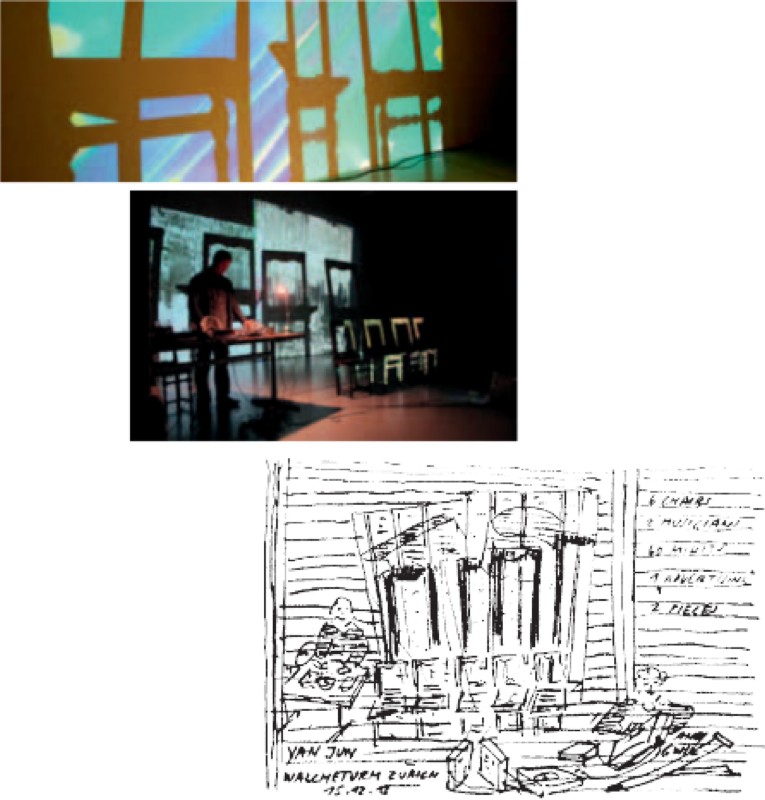

Concert for five chairs and two players,Walcheturm, Zurich

(1–3) Concert situation withYan Jun and five chairs,Walcheturm, Zurich.

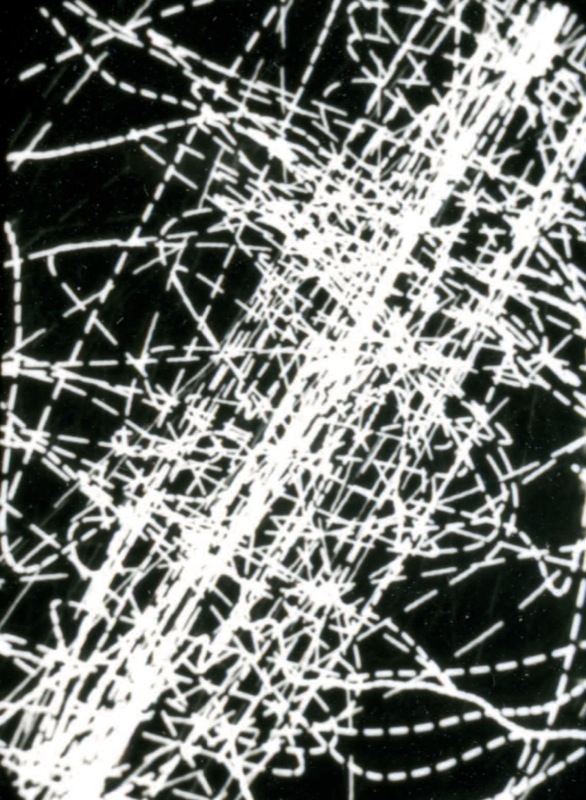

The (Historical) Sound of Images

by Peter Kraut

by Peter Kraut

One of the most important works in the history of associating sound and the visual arts is Robert Morris’s Box with the Sound of Its Own Making (1961). Inside a small wooden box is a loudspeaker that reproduces the sounds produced as the box was being made. As both sculpture and process, sound and matter, the box associates the passage of time with static existence. And had the box been black, rather than brown, we would have had the proverbial Black Box, in which things unfathomable occur and converge.Today, interface has become the generally accepted term to describe something similar— the crossover point between things and media in which connections and translations occur. Many other artists since Robert Morris have explored the field in which sound and sculpture, performance and music, image and sound and technology converge in a variety of ways; video and sound installations, for instance, now look back on their own long history. Andy Guhl is part of that tradition, and for decades he has been looking for innovative ways of extracting new aspects from the conflation of image and sound. He does so not as an engineer who first sketches out his blueprints and draws up his shopping lists; rather, he adopts the pragmatically philosophical approach of the handyman, in the best sense of the word, i.e. someone who works with whatever materials are to hand.These are ordinary and “common” materials, reminiscent of the familiar technology environment of stereo systems, overhead projectors, surveillance cameras and computer mice. Andy Guhl uses them to build a multisensory system which he then feeds with inputs in real time.Thus he creates a precarious equilibrium between hearing and seeing, stasis and flux, silence and volume that is unpredictable for the audience—and packed full of surprises.

So Andy Guhl picks up on a much older tradition which, under the keyword of “synaesthesia,” stretches far back into history.This technical term designates the ability to perceive or portray phenomena using senses and means not specifically intended for that purpose, like seeing sounds, sounding colors, smelling images, etc. In the association of seeing and hearing, seeing has long predominated over hearing. One of the reasons is that modern science, as it emerged, ascribed a far greater importance to the visual than the aural. A society that hands down its body of knowledge first and foremost in textual form places greater trust in the eye than in the ear.Thus the listeners and speakers of the Middle Ages gradually became writers and readers in the linear world of the textual, who recorded their findings in written form, even those on acoustics. Impressive, for instance, are the experiments described by Ernst Chladni in his Entdeckungen über dieTheorie des Klanges [Discoveries in theTheory

of Sound] in Leipzig around 1770. He would run a violin bow along the edge of plates made of glass and metal covered with fine sand.The patterns created by the vibrations provided

environment has long succeeded in casting out: he is not

a user, but a subversive arranger and Luddite thwarting technological conventions. He is a timely reminder, then, that design and use are inscribed and prescribed within the simple things. And while they may well fulfill their intended purpose as a result, artistic freedom begins at the point where such boundaries are transcended.

Distilled from a Conversation on November 5, 2013

by Peter Hubacher

by Peter Hubacher

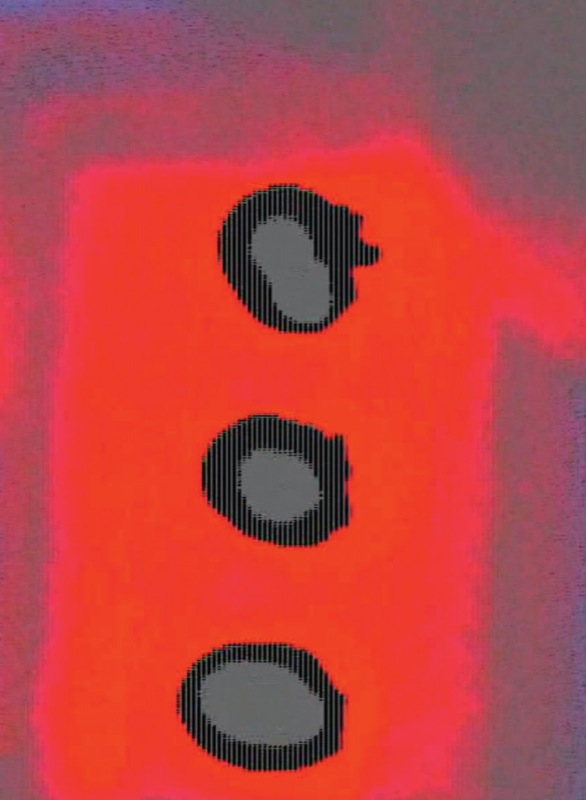

Instruments, full screen, scanner, analog, rotary dial phone, “Translatin,” emulsion, improvisation, reactive paper, organ, reforming, noisy, anatomy, archaeology, visual work, control, combination, generator, prism, sound check, 1972, double bass, percussion, primed instrument, membrane, sound material, improvisation, jazz, chaos, free music, colored light, psychedelic art, sober, filter, piano destruction, vibrating string, currents, proximities, tonalities, error, signal, feel, tension, tambourine, drum, marimba, sound board, camera, direction of movement, flow process, beat, state of suspense, glissando, tension spring, electronics, brass movement, energetic distribution, blues soul groove, low frequency, playing in the forest, open air, echo without reverberations, magnetic core memory, wall object, metal part, geometric regularity, memory, line spectrum, perception, scales, models, Albrecht Dürer, “Melancholia I,” facts, studio, condenser, horn, interference, color, dream, memory, mechanical, receiver, sound installation, radio, on the object, rotations, instrument table, ethnological music, sound on vision, transistor, converter, memory, reading head, optical element, wafer board, description, correction, transmission distortion, transformation, telescope, module, open up, cassette player, engine, band, low current soldering, text, filter effects, induction currents, switch, cable, plugs, sockets, circuit, magnetic field effects, sound box, photo- electric resistance, integrated circuit, resonant circuit, vibratory fields, contact microphone, record player, performance, process, 35 minute performance time, frequency response, recording device, station, engine, spotlight, compressed air, gesture, randomizer, exposing a heliogram, system sketch, loudspeaker, high frequency air cleaner, board, cathode beam, magnetic coil, horizontal-vertical deflection, endless band, sinus sound, remake, terrestrial signal, video, studio, loop, oscilloscope, recording and playback process, interpreting, spectral analysis, tuner, hard disc, number patterns, timer, medium wave, points, image converter, infrared remote control, differential transformer, steady tone,

modulation, chip entanglement, signal output, LCD screen,

ethnic, image projection, video print, cats’ eyes, sensors, brown

coal seam, transfer.

pink = important

yellow = unimportant

blue = common

strike through = wrong

yellow = unimportant

blue = common

strike through = wrong

Sliced Cat Brain. Microscopic sample of a cat brain projected on stomach, portrait.

2013

Audiovisual recordings on a five-hour locomotive train ride, Samedan to Chur

My first sonic Lok, exhibition in Bahnmuseum Albula in Bergün

ArtistTalk with PiusTschumi, Bahnmuseum Albula in Bergün

My first sonic Lok, exhibition in Bahnmuseum Albula in Bergün

ArtistTalk with PiusTschumi, Bahnmuseum Albula in Bergün

My first sonic Lok

Andy Guhl at the Bahnmuseum Albula

by Nora Hauswirth and PiusTschumi

Andy Guhl at the Bahnmuseum Albula

by Nora Hauswirth and PiusTschumi

It is only fitting that for his first exhibition at the Bahnmuseum Albula, a railway technology museum located in Bergün, Switzerland, avant-garde St. Gallen artist and musician Andy Guhl has turned a train locomotive into a musical instrument.

Guhl creates an unusual and innovative audiovisual sound experience building from the inaudible electromagnetic oscillations of a sixty-five ton, twenty-four-hundred horsepower locomotive. By means of the locomotive, Guhl composes a listening and viewing experience in which various motifs are perceptible, such as the power when the engine starts up, the different states of the motor, and the condition of the tracks.

The work is presented in one of the museum’s temporary exhibition rooms, where Guhl has installed a five-channel video piece together with a selection of his own photographs. In the installation, the artist takes the viewer on a journey from Samedan to Landquart, Switzerland: technology and nature appear in poetic sights and sounds as the landscape passes at different speeds.

At least since Pacific 231, in which Arthur Honegger (1892–1955) musically transformed a railway trip with a Pacific steam engine into a tone poem, the locomotive has been a fascinating motif in classical music.The engine and its rhythmical power, as well as the full-throttle journey, were all portrayed vividly and impressively in Honegger’s composition.The work was created in 1923 and had its premiere at the Paris Opera on May 8, 1924.Today, the Franco-Swiss composer, who admitted to having a passionate love for locomotives, features on the banknote for twenty Swiss francs.